Feed and Nutrition

The greatest single cost in keeping a horse is feed. You must learn exactly what nutrients a horse requires as well as how to compare costs and judge quality. You also need to understand how a horse digests its food, because its digestive process is what makes the horse one of the most complicated of the domesticated animals to feed.

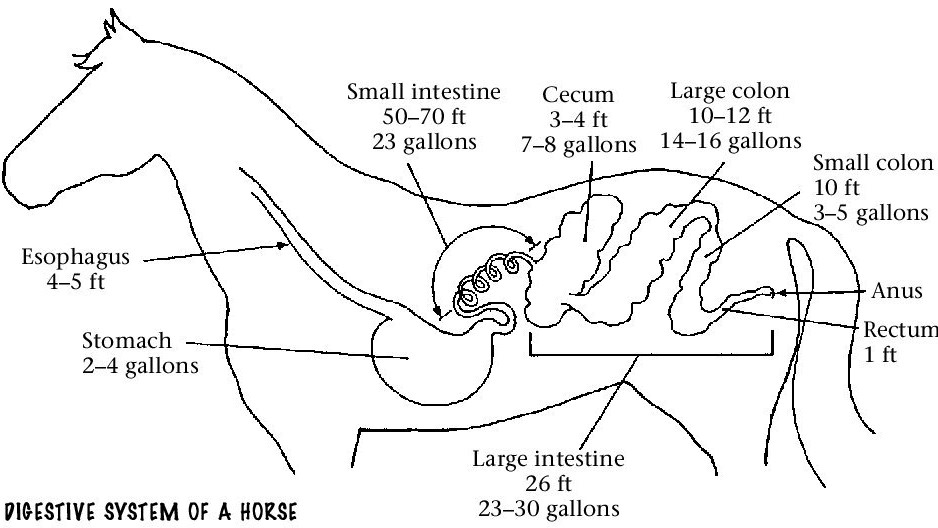

The Digestive System

Two basic types of digestive systems are found in animals. One is the simple stomach system typical in pigs and humans. The other is the ruminant system typical in cattle and sheep.

The simple stomach is adapted to digest less bulky feeds such as vegetables and grains, and its capacity is small. Digestion occurs by digestive juices. The ruminant system is designed to digest bulky, coarse feed such as grass and hay, and it has a much larger capacity. Much of the digestion in a ruminant occurs through fermentation by microbes (bacteria and protozoa) rather than by digestive juices.

The horse’s rather unusual digestive system is a combination of these two types.

It is considered a nonruminant herbivore, or hindgut fermentor. The hindgut consists of the large intestine (cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal), while the foregut consists of the stomach and small intestine.

The horse has a simple, small stomach and a large cecum and colon. Food passes through a horse much faster than in ruminants, so its digestion is less efficient. In total, food material spends about 1 to 6 hours in the foregut and 18 to 36 hours in the hindgut.

A horse’s digestive process begins in its mouth. Unlike a cow, which can wad up and swallow hay or grass without chewing it thoroughly, the horse must chew its food to

reduce its bulkiness and add saliva to start the breakdown. If food is not broken up, the horse does not digest it well and gains few nutrients from it.

The chewed food goes down the esophagus to the stomach, where digestive juices continue the process. A horse’s stomach is small. The stomach of a 1,000-pound horse holds only 2 to 4 gallons of food. Its small stomach limits the amount of food a horse can eat at one time. A horse is naturally a grazing animal, eating small bites here and there for 15 to 20 hours a day; so, domesticated horses do best when fed small amounts several times a day.

The stomach begins to empty when it is about two-thirds full. This is a safety

mechanism to keep the stomach from getting too full and rupturing (because a horse cannot vomit). Food stays in the stomach only a short time before moving on to the small intestine.

In the small intestine, most of the starch, sugar, fats, vitamins, and minerals are absorbed.

About half the protein also is digested here and absorbed into the bloodstream. The small intestine is about 50 to 70 feet long and holds 10 to 23 gallons.

Next, food moves through the large intestine, starting in the cecum and progressing

through the large and then small colon. Here is where fermentation—microbial action more like that of a cow—takes place. Bacteria and other organisms digest the fibrous material. The remaining protein and some minerals are absorbed here.

The entire hindgut can hold about 23 to 30 gallons. The cecum, which is 3 to 4 feet long, holds 7 to 8 gallons.

The 10- to 12-foot large colon holds 14 to 16 gallons, and the 10-foot small colon holds 3 to 5 gallons.

Because of the horse’s combination type digestive system, it can eat both grains and forage. However, this digestive system makes the horse prone to health problems such as colic and founder. So, there are several things you must keep in mind when determining what to feed your horse.

1. A horse’s digestive system works well when its feed consists mainly of grass and hay. The system does not work well when too much grain is added to the diet. (Grains are very high in starch. Excess starch cannot be digested in the foregut, so it is passed to the hindgut. Extra starch in the hindgut increases the number of starch-digesting bacteria. These produce lactic acid, which makes the large intestine more acidic. The fiber-digesting bacteria can’t survive in acidic conditions, and when they die, they release toxins.

Colic and/or founder are often the result.)

2. The horse has no gall bladder. This makes it hard to digest and get nutrients from a diet that is high in fat.

3. Remember that the digestibility of the food is just as important as the food’s nutrient content. The horse gets no benefit from foods it cannot digest.

Nutrients

There are six essential nutrients: proteins, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water. A horse must receive all nutrients in the proper amounts, as both too little and too much can cause health problems.

A balanced ration supplies all required nutrients in the proper amounts for each individual horse. A maintenance diet provides the minimum amount needed to keep the horse in the same physical condition.

Protein

Proteins are necessary for all of life’s processes. They are especially important for growth, reproduction, and lactation. They are required for muscle repair and building. The requirement for most adult horses is 8 to 10 percent of the ration.

Good-quality hays and grains have enough protein for most horses. Cultivated grass hay contains about 9 percent protein, and alfalfa averages about 15 percent. Native grass hay averages only 7 percent and may be as low as 5 percent. Therefore, it must be supplemented.

Horses need more protein at certain times of their lives. Mares should receive 11 percent protein in their last 90 days of pregnancy and 14 percent while lactating. Growing foals should receive 18 percent protein, as most tissue growth occurs at an early age. Grain alone, with only 10 percent protein, cannot supply these extra needs. Common sources of extra protein are legume hays, pasture, soybean meal, and linseed meal.

Signs that a horse is deficient in protein include weight loss; a rough, coarse coat; slow growth; a decline in the horse’s performance; and a decrease in a mare’s milk production.

Horses also can suffer from too much protein in their diet. Too much protein can lead to dehydration and an electrolyte imbalance.

Signs of too much protein include drinking more water, urinating larger amounts, and sweating more profusely.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates are the horse’s main source of energy. After a horse’s basic requirement for maintenance is met, extra energy is used for work, growth, and milk production, or stored as body fat. The amount of energy a horse requires is determined by the horse’s size and by the amount and kind of work it performs.

Carbohydrates include sugars, starches, and cellulose. Glucose, a simple sugar, is the main building block of carbohydrates and the chief form in which the horse absorbs carbohydrates.

Grains such as oats, barley, and corn may be as much as 60 percent carbohydrates. They are excellent sources of energy. Due to the relatively small size of the horse’s digestive system, an increased need for energy is met by adding grain and decreasing the amount of hay.

Fats

Fats are the densest source of energy.

They contain about twice as many calories per pound as carbohydrates and protein, and they provide more body heat. Premixed feeds usually contain 2 to 6 percent fat, which is easily enough to maintain a horse. If a horse’s diet lacks fat, the horse may develop rough skin and a thin, rough hair coat.

Vitamins

Vitamins are required in small amounts to help regulate chemical reactions within the body. Each vitamin has a unique function and cannot be replaced with another. Also,

a deficiency of one vitamin can interfere with another’s function. Deficiencies affect

growth, reproduction, and general health, but symptoms can be difficult to diagnose.

Most horses get enough vitamins in their normal diet. Green leafy forage contains most vitamins and, along with sunshine, usually supplies a horse with all it needs. You may need to give your horse a vitamin supplement if your feed is low quality, if the horse is under stress, if it is not eating well, or if it is doing strenuous work.

Do not feed a vitamin supplement unless it is needed. Feeding more than the recommended allowance is a waste of money and can cause health problems.

Vitamin A

Green grass and legume hay contain carotene, which is converted to vitamin A in the animal’s body. Vitamin A maintains the health of mucous membranes (such

as those found in the respiratory tract), and increases resistance to respiratory infections. Severe deficiency may cause night blindness, reproductive difficulties,

poor hoof development, difficult breathing, incoordination, and/or poor appetite. Alfalfa leaf meal is used in pelleted commercial supplements to supply this vitamin.

Oxidation (exposure to air) destroys vitamin A. Therefore, hay that has sat for more than a year has very little vitamin A left in it.

Vitamin D

Sunlight is the natural source of vitamin D. Horses kept inside may be deficient and need a supplement. This vitamin helps develop sound bones and teeth, so requirements are high during growth. A serious deficiency may cause rickets, slow growth, or weak bones and teeth. Cod liver oil or dried yeast with vitamin D added are effective supplements.

Vitamin E

Green pasture or hay supplies vitamin E. The amount of vitamin E in hay decreases with plant maturity and with the length of storage time. Poor feed or stress may cause a deficiency. Broodmares, stallions, or racehorses may need additional vitamin E to aid in the development and maintenance of muscle. Soybean meal or wheat germ oil provide additional amounts.

Vitamin K

Vitamin K is needed for the production of blood clots. Internal bleeding may occur if there is a deficiency.

Vitamin C

A horse’s liver produces vitamin C. A horse almost always has a sufficient quantity, so there is no need to supplement this vitamin.

Minerals

Minerals are essential for sound bones, teeth, and tissues. They are needed for maintenance of body structure, fluid balance, nerve conduction, and muscle contraction. Minerals are important at all stages of life, but pregnant mares have increased requirements and lactating mares even more.

Proper mineral balance is very important, because one mineral can counteract the

effect of another. For example, too much phosphorous reduces the amount of calcium and other minerals that a horse can absorb. Consult a veterinarian or do further research to determine the proper supplements for your

horse. Most horses get enough minerals in their regular diet, with the exception of salt.

Salt

Horses may lose 1 to 2 ounces of salt per day in sweat. Lack of salt may contribute to heat stress, poor appetite, or a rough coat.

Most horse feeds are deficient in salt, so horses need free access to salt in block or granular form. Iodized or trace mineralized salt is recommended.

Salt should always be available in summer or if the horse is being worked hard. Loose salt may be better in the winter, because the horse may not lick a block as much.

The salt requirement varies according to temperature and the amount of work. On the average, a horse consumes 2 ounces of salt daily or about 1 pound per week. Horses on green pasture usually require more salt.

Protect salt and mineral supplies from rain or other moisture to prevent waste.

Calcium and Phosphorus

The ratio of calcium to phosphorus in the diet is critical. In general, the ration should be two parts calcium to one part phosphorus for weanlings and yearlings. As the horse matures, it needs much less phosphorous in relation to calcium. The amount of phosphorus should never exceed the amount of calcium.

Rickets, fragile bones, or other abnormal bone development can occur from a calcium– phosphorus imbalance. Hormone imbalance may also result.

High-quality hay meets the calcium needs of the mature horse, but grass hays and grains usually do not supply enough calcium for the growing horse and pregnant or nursing mare. Legume hay is a rich source of calcium.

Grains are a good source of phosphorus.

However, a diet with too much grain is likely to produce a calcium–phosphorous imbalance.

A good source of supplemental calcium and phosphorous for growing horses is dicalcium phosphate mixed half-and-half with salt to make it palatable. One-fourth cup per day supplies the needs of a pregnant or nursing mare. Foals require less. Commercial mixes also are available.

Iodine

Feeds grown on Pacific Northwest soils are deficient in iodine. Lack of iodine may cause goiter or stillborn or weak foals. Iodized salt is recommended.

Iron

Most grass and hay are iron-rich, but a mare’s milk is deficient. Make sure foals have access to trace-mineralized salt, which contains iron. The body uses iron to form hemoglobin, which enables the blood to carry oxygen, so a deficiency may cause anemia.

Selenium

Some Northwest soils are deficient in this mineral, which is important for proper

utilization of vitamin E. Pregnant mares, foals, and young horses particularly need selenium to help prevent skeletal and muscle disorders. Some commercial feed supplements contain selenium, or it may be injected.

There is a very narrow range of normal levels of selenium. Too much can be dangerous (it is toxic), so be careful not to give more than is needed.

Water

Water is as essential to good nutrition as any solid feed. In fact, water is considered the most important nutrient, as a horse cannot live long without it. It is the major component of blood, which carries nutrients to all parts of the body. It picks up waste products and helps eliminate them. Be sure that fresh, clean water is available to your horse at all times.

Normally, a mature horse drinks 10 to 12 gallons of water a day. When the temperature is high or during work, it can drink considerably more than that. A lactating mare also drinks more water than usual.

Types of Feed

Feed includes roughages (pasture and hay), grains or concentrates, and supplements. Whichever feeds you choose, be sure they are good quality. The quality of the feed is far more important than the quantity fed.

Pasture

Using pasture reduces feed costs, particularly if the pasture is well managed. A horse that grazes freely during the summer requires little else to meet its nutritional needs.

Pastures may include both native ranges and improved fields. Grass grown in fertilized fields is more nutritious than native grass.

Remove horses from pasture during the winter to avoid damage from trampling.

Winter growth is high in water content and not very nutritious, so you would need a hay supplement and possibly grain and other supplements also. Allow the grass to become well established before turning horses out in the spring.

When returning the horse to pasture in the spring, follow a careful schedule to avoid founder. Feed the horse first, then allow it only 1 to 2 hours grazing the first week, 2 to 4 hours the second week, and 6 to 8 hours the third week. Shorten the time if the horse’s crestline thickens or its pings are loose.

Hay

Hay is forage that has been cut, dried, and baled. There are two categories of hay: legumes and grasses. Legumes, such as alfalfa and clover, are higher in protein, calcium, and vitamin A. Grass hay is higher in fiber content and lower in digestible energy. Common grass hays are timothy, orchardgrass, fescue, bentgrass, and ryegrass.

Good-quality grass hay has enough nutrients to sustain a horse. The horse can eat more without getting fat, which is better for the horse’s digestion and helps relieve boredom.

Take care when feeding alfalfa to make sure the protein level isn’t too high and the horse doesn’t get overfed. Mixing alfalfa and grass hay together is often a good choice.

Hay is most nutritious when it is cut before maturity. The older a hay is when it is cut, the more fiber it has and the less digestible it is.

Older hay also has less protein and phosphorus. Hay should have a high leaf-to-stem ratio.

Most of the nutrients are in the leaves, and they are also more palatable. Stems are hard to digest and low in nutritional value. So, leafy hay gives more value per ton.

Quality hay should be green: the greener the hay, the higher it is in vitamins, especially vitamin A. Hay that has been left in the rain will not be green and will have few vitamins left in it.

All hay should be sweet smelling and free of dust, dirt, and foreign objects. It should contain no weeds, especially poisonous types. Never feed moldy hay, as it can cause heaves, colic, and abortion.

Chopped hay has been cut into pieces about an inch long and then bagged. It can be quite dusty, so molasses or oil usually is added. This product can be fed to horses with respiratory problems or that have trouble chewing. You can mix grain in with chopped hay when feeding.

Grains and Concentrates

Grain generally is not necessary for mature horses, and they certainly need far less than most owners think they do. Lactating mares, young growing horses, and hardworking horses need grain added to their diet. Do not feed grain within 1 hour before or after hard work.

Grains and concentrates (pelleted or sweet feed) are low in fiber, highly digestible, and less bulky than roughage. The energy value of different grains varies widely. Know the nutritional value of each and feed only what is needed. No more than half the ration should be concentrates.

Oats

This popular grain contains the correct balance of nutrients and is a relatively safe feed. Horses can digest the starch from oats in the foregut, leading to fewer digestion problems.

Oats are higher in fiber, protein, and minerals than many other grains, and they are highly digestible and palatable.

Oats can be fed whole, rolled, or crimped. Rolled oats are recommended for very young or old horses that cannot chew well. Whole

oats are generally less dusty and do not mold as easily.

Varieties of oats include gray, white, and red. White are most commonly used because they are the softest and easiest to roll.

Barley

Barley is higher in energy than oats, so you don’t need to feed as much. It is moderate in fiber, nutritious, and palatable. It can help a horse gain weight.

Feed only steamrolled or crimped barley.

The hard hulls of whole barley must be processed or they are very hard to digest.

Corn

Corn is a high-energy carbohydrate that is relatively expensive in the Northwest. It is low in fiber, protein, calcium, and other minerals. It has a high calorie content, so it is fattening and can cause obesity. Use corn with caution, as it is easy to overfeed.

Corn should be cracked or rolled. This makes it somewhat dusty, but it is a satisfactory feed when used in combination with other feeds and molasses. Never feed moldy corn: it can be lethal.

Wheat

Wheat is higher in energy than corn. It generally is not used as a grain for horses due to its high cost. It is best used in a feed mixture, as it is not very palatable by itself. The hard kernels must be processed, or the horse cannot digest them.

Wheat Bran

This is the coarse outer covering of the wheat kernel. It contains about 16 percent protein, but only about 50 percent is digestible. It also contains a good amount of phosphorus. Because it is high in bulk, it is a good laxative. Bran mash is prepared by mixing bran with hot water to the consistency of oatmeal and allowing it to steam under cover until cool.

Rye

Although it is high in protein, rye is not very palatable and is seldom used as a horse grain. It is susceptible to the “ergot” fungus which can cause severe health problems.

Alfalfa Pellets

Alfalfa hay is mowed and chopped in the field, then dried at a dehydrating plant, ground, and formed into pellets. The pellets can become quite dusty, which adversely affects horses with respiratory problems. A horse’s diet cannot consist solely of alfalfa pellets, because the particles in the pellets are not large enough to maintain normal digestion.

Alfalfa Cubes

An native to pellets, these are made by coarsely chopping alfalfa hay and then compressing it into small cubes (usually about 2 x 2 inches). This process does not reduce the nutritional value of the feed; it remains the same as hay. The material in the cubes is large enough to maintain normal digestion. While alfalfa is the most common, cubes can be made from other types of hay as well, and grass and alfalfa may be mixed in a cubed feed.

There are several advantages to feeding cubes over baled hay. Generally, there is less waste, and the quality tends to be more consistent. Cubes are easier to handle, it is easy to monitor the exact amount being fed, and they require less storage space. Cubes also have little dust, making them a much better choice than pellets for horses with respiratory problems.

Disadvantages to feeding cubes are that horses can choke from eating them too fast, they are more expensive than hay, and horses can become bored because they spend less time eating. Also, you must carefully regulate how much is fed, as it is easy for a horse to overeat and become fat or have digestive problems.

Beet Pulp Pellets

Beet pulp is the fibrous material left after processing sugar beets. It is an easily digestible fiber supplement that can replace other forage in the horse’s diet. Up to 25 percent of a horse’s feed can be beet pulp. It is low in crude protein (usually 7 to 10 percent) and high in fiber (around 22 percent).

A common misconception about beet pulp pellets is that they cause choke, a condition in which food gets stuck in the horse’s esophagus. Actually, choke often is a behavior problem, as it usually occurs in horses that bolt their food (swallow without chewing). Slow eaters seldom choke.

Another common myth about beet pulp pellets is that they expand in the stomach if they are not soaked properly before feeding, causing a horse’s stomach to rupture. Studies show that the pellets are safe to feed without soaking as long as the horse has free access to water. Most people still prefer to soak them, because it makes them more palatable.

To soak pellets, place them in a tub and add twice as much water as pellets. You may use warm or cold water, but do not use hot water: it destroys the nutrients. Soak the pellets for at least 2 hours or until they no longer look like pellets. Soak only enough pellets for one feeding. If they soak for over 12 hours, they ferment and are unpalatable to the horse.

Beet pulp pellets often help add and keep weight on hard keepers. They are also a good supplement for poor-quality hay. Horses with dental problems often do well on beet pulp pellets, because they are easy to chew. They are not a good choice for horses doing strenuous work.

Supplements

Add supplements to your horse’s feed only when something is missing from its diet. Use them only on the advice of a veterinarian.

Feeding unnecessary supplements can disrupt the balance of vitamins and minerals and damage the horse’s health. If the horse cannot rid itself of the excess nutrients, they can build up to toxic levels in the body. They are also fairly expensive.

Common protein supplements are soybean meal, linseed meal, cottonseed meal, and brewer’s grain. Common fat supplements are rice bran, flaxseed, and vegetable oil.

Soybean Meal

Soybean meal is the most common protein supplement. At 44 percent protein, it helps meet the protein requirements of foals and lactating mares without adding too much bulk. One to 2 cups twice a day should supply what they need. Soybean meal contains lysine (lie- SEEN), an amino acid which affects growth. Be sure adequate calcium and phosphorous are available also.

Linseed Meal

This protein supplement has laxative qualities. Linseed meal averages 35 percent protein, but it is less digestible than soybean meal, so more must be fed. It is deficient in lysine and should not be the only protein supplement given to mares and foals.

Modern solvent processing techniques have greatly reduced the fat content. Only the old “expeller” process leaves 10 percent fat, which adds gloss to the coat.

Cottonseed Meal

This supplement averages 41 to 48 percent protein. It is rich in phosphorous and low in lysine. It is not popular as a horse feed, because certain seeds may contain a toxic substance.

Brewer’s Grain

Brewer’s grain is the mash removed from malt when making beer. It is palatable and nutritious, containing around 25 percent protein, 13 percent fat, and many B vitamins.

Rice Bran

Rice bran has up to 20 percent crude fat. It is a popular fat supplement and an excellent source of vitamin E. Rice bran can help a horse maintain weight and give it a sleek, glossy coat. It is not as messy to feed as vegetable oil, and it keeps longer. It is also highly palatable.

A drawback to rice bran is that it can a calcium–phosphorous imbalance. Many manufacturers add calcium to the rice bran to help maintain the proper balance. To reduce the chance of mineral overload, do not feed more than 2 pounds per day.

Flaxseed

These small, hard seeds must be ground, cooked, or soaked in water so the horse can digest them. Flaxseed has a high concentration of omega-3 fatty acids which the horse cannot produce on its own. It is high in soluble fiber which gels in water and is thought to reduce the risk of sand colic. It is also a good source of vitamin E.

Vegetable Oil

This is probably the most common fat supplement. It is added as a top dressing to grain rations to give more sheen to a horse’s coat. Do not feed more than 2 cups per

day. Corn, soybean, and safflower oils are commonly used. Oils can turn rancid if they are stored too long.

Mixed and Complete Feeds

Mixed feeds

Mixed feeds are produced commercially for convenience, and they are more expensive. Grain mixes are often made of corn, oats, and barley, so horse people call them C.O.B. Dry

C.O.B. contains just these grains; wet C.O.B. has molasses added. Molasses is a byproduct of processing sugar.

It is used mostly as an appetizer (it can help a horse eat grain with medication or supplements added) and to bind together mixes which tend to be dusty. Avoid molasses content higher than 5 percent. Molasses is quickly converted to sugar in the horse’s foregut, and too much can cause digestive and performance problems.

The ingredients and nutrient content in mixed feeds are on the feed tag as required by law. Buy only the type that fits the needs of your individual horse.

Complete Feeds

Complete feeds are hay and concentrates mixed in one. They can be helpful to horses with dental problems, as they are easier to chew.

Complete feeds meet the nutritional needs of a horse as well as hay does, but they do not have many of the benefits. Since the horse chews less, there is less saliva mixed in with the swallowed feed. The chemicals in saliva act as

a buffer against stomach acids and lessen the risk of ulcers. Horses also spend less time eating complete feeds, so they are likely to become bored and develop stall vices or other behavior problems.

There are many types of mixed and complete feeds designed for horses with specific needs (such as senior or young horses and pregnant mares).

With both hay and grain, make sure you feed by weight and not by volume. A flake of hay could weigh from 2 to 10 pounds. A can of grain could be 2 pounds of oats or 5 pounds of corn, depending on the size of the can and the quality of the grain. You can use the flake and can to measure feed as long as you have weighed it first to get an average.

If it is practical, feed each horse indivi- dually. That way there will be no competition for food. Timid horses will get their share, and more aggressive horses will not eat more than they should.

A horse that bolts its food (swallows without chewing) is prone to choking. Slow the horse’s eating by adding rocks or salt blocks to the feed box.

If you change your horse’s feed, it is critical to do it gradually. A horse’s digestive system cannot handle sudden changes, and colic can be the result of a change made too rapidly. Take at least several days and up to 2 weeks to switch from one type of feed to another or to move

a horse on and off pasture. Slowly increase or decrease the amount fed, as well. When the amount of work or exercise changes, adjust the feed ration, too.

Amount to Feed

The amount of feed a horse requires varies greatly. When determining how much to feed your horse, consider the following factors.

Size

Feed a horse approximately 2 percent of its body weight per day. For example, a 1,000-pound horse would require about 20 pounds of feed with no more than

0.5 percent concentrates. You can use a heart girth measuring tape, available at most feed stores, to help estimate your horse’s weight.

Feeding your Horse

Remember that horses evolved as grazing animals and have relatively small stomachs. To stay healthy, they need to eat frequent small meals. Feed your horse at least twice a day, giving approximately half of the day’s ration at each feeding. Feed hard-working horses most of their hay at night when they have plenty of time to eat it.

Feed on a regular schedule, leaving at least an hour between feeding and exercise. Horses are easily upset by changes in routine, so feed your horses at the same time every day, including weekends and holidays. If you feed twice a day, space the feedings as close to 12 hours apart as possible.

Age

A horse’s age determines how much as well as what type of feed you should use. Young horses need more protein for growth, while older horses need feed that is easier to digest.

Work

The harder a horse is worked, the higher its nutritional requirement. An idle horse is

seldom used. Light use is from once a week up to 3 hours daily without stress. Medium use is 3 to 5 hours daily for light showing, pleasure, or trail riding. Heavy use is showing or racing full time, or working 5 to 8 hours daily.

Parasites

Both internal and external parasites can affect how much feed a horse needs. Horses on good deworming programs require less feed.

Horses whose intestines have been scarred by parasites require more feed because they absorb fewer nutrients.

Other

Other factors that affect how much to feed include:

• Time of year (more feed is required in the winter)

• Condition of the horse’s teeth

• Temperament of the horse

• Breed of horse

• Amount of grazing the horse is allowed

• Environmental factors such as heat, wind, and moisture

• Vices such as cribbing or stall weaving (require increased nutrition)

• Horse is an easy keeper (requires less than the average amount of feed)

• Horse is a hard keeper (requires more than the average amount of feed)

Check your horse’s body condition often to be sure it is maintaining a healthy weight. Never feed your horse more than it needs.

Too much weight puts strain on all the body systems, leading to heart, respiratory, and digestive illnesses. The risk of lameness also increases with excess body weight. A good rule of thumb is that you shouldn’t be able to see a horse’s ribs, but you should be able to feel them.

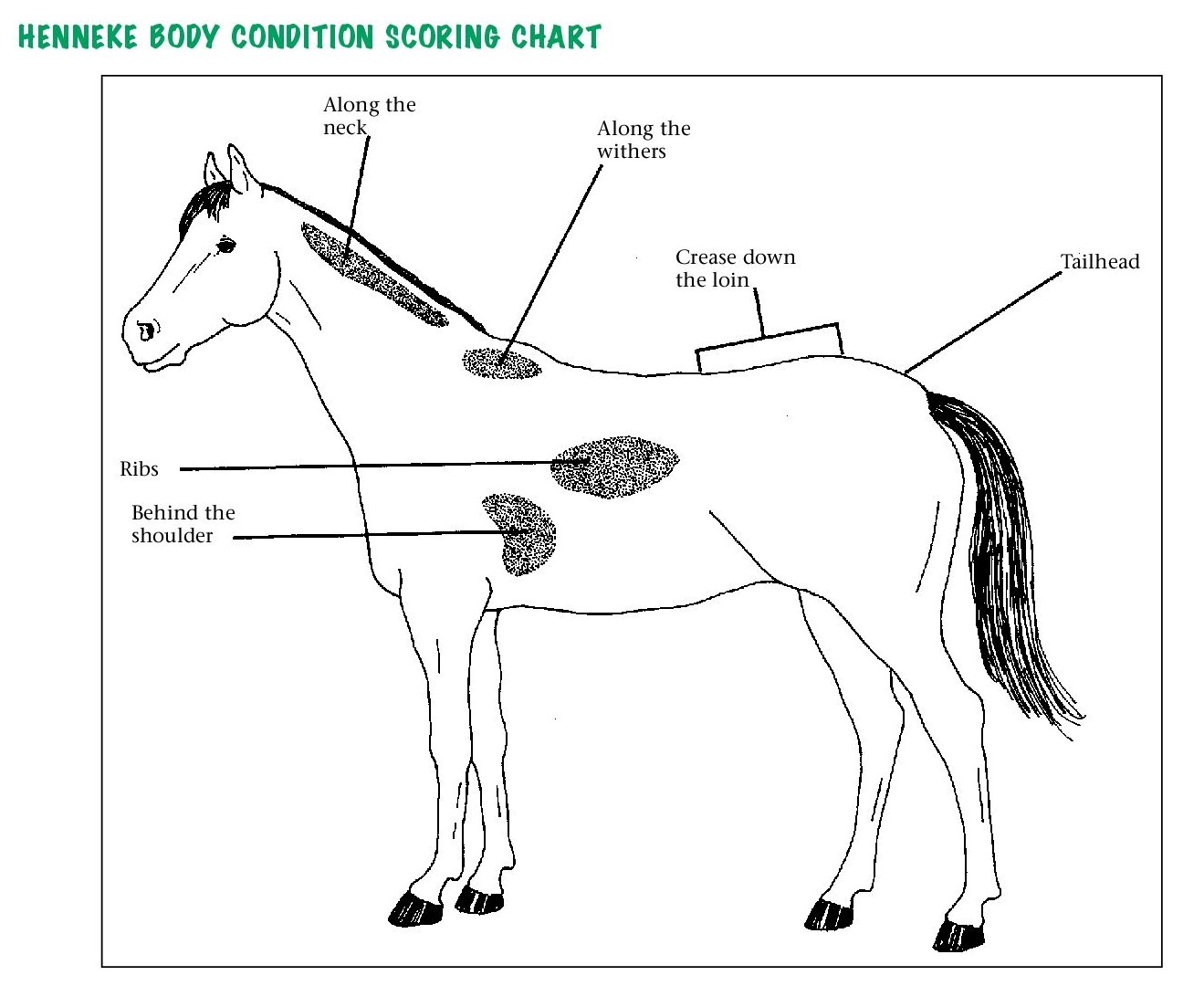

Henneke Body condition scoring system

One way to determine the condition of your horse is with the Henneke Body Condition Scoring System. This system,

accepted in a court of law, was developed in 1983 by Don Henneke, Ph.D. and is now used almost universally. The Henneke scores have replaced subjective terms such as “skinny,” “fat,” “emaciated,” or “plump.”

The Henneke system uses both visual appraisal and feel. Six parts of the horse are rated on a scale of 1 to 9: the neck, withers, shoulder, ribs, loin, and tailhead.

A score between 4 and 7 is acceptable, with 5 being ideal. A score of 1 is poor (emaciated), and a score of 9 is extremely fat (obese).

Score descriptions

1. Poor—Emaciated. Prominent spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and hooks and pins. Noticeable bone structure on withers, shoulders, and neck. No fatty tissues can be palpated.

2. Very thin—Emaciated. Slight fat covering over base of spinous processes. Transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae feel rounded. Prominent spinous processes, ribs, tailhead, and hooks and pins. Withers, shoulder, and neck structures faintly discernible.

3. Thin—Fat built up about halfway on spinous processes; transverse processes cannot be felt. Slight fat cover over ribs. Spinous processes and ribs easily discernible. Tailhead prominent, but individual vertebrae cannot be visually identified. Hook bones appear rounded, but easily discernible. Pin bones not distinguishable. Withers, shoulders, and neck accentuated.

4. Moderately thin—Negative crease along back. Faint outline of ribs discernible. Tailhead prominence depends on conformation; fat can be felt around it. Hook bones not discernible. Withers, shoulders, and neck not obviously thin.

5. Moderate—Back is level. Ribs cannot be distinguished visually, but can be felt easily. Fat around tailhead beginning to feel spongy. Withers appear rounded over spinous processes. Shoulders and neck blend smoothly into body.

6. Moderate to fleshy—May have slight crease down back. Fat over ribs feels spongy. Fat around tailhead feels soft. Fat beginning to be deposited along the sides of the withers, behind the shoulders, and along the sides of the neck.

7. Fleshy—May have crease down back. Individual ribs can be felt, but noticeable filling between ribs with fat. Fat around tailhead is soft. Fat deposits along withers, behind shoulders, and along the neck.

8. Fat—Crease down back. Difficult to palpate ribs. Fat around tailhead very soft. Area along withers filled with fat. Area behind shoulder filled in flush. Noticeable thickening of neck. Fat deposited along inner buttocks.

9. Extremely fat—Obvious crease down back. Patchy fat appearing over ribs. Bulging fat around tailhead, along withers, behind shoulders, and along neck. Fat along inner buttocks may rub together. Flank filled in flush.

.jpg)